Unofficial - F5 Certification Exam Prep Material > F5 301B - BIG-IP LTM Specialist: Maintain and Troubleshoot Exam Study Guide - Created 11/01/19 Source | Edit on

Section 2 - Identify and Resolve Application Issues¶

Objective - 2.01 Determine which iRule to use to resolve an application issue¶

2.01 - Determine which iRule events and commands to use

https://support.f5.com/kb/en-us/products/big-ip_ltm/manuals/product/ltm-concepts-11-5-0/18.html

iRule Events and Commands

An iRule is a powerful and flexible feature within the BIG-IP operating system that you can use to manage your network traffic. The iRules feature not only allows you to select pools based on header data, but also allows you to direct traffic by searching on any type of content data that you define. Thus, the iRules feature significantly enhances your ability to customize your content switching to suit your exact needs.

Important: For complete and detailed information on iRules syntax, see the F5 DevCentral web site, http://devcentral.f5.com. Note that iRules must conform to standard Tcl grammar rules; therefore, for more information on Tcl syntax, see http://tmml.sourceforge.net/doc/tcl/index.html.

An iRule is a script that you write if you want individual connections to target a pool other than the default pool defined for a virtual server. iRules allow you to more directly specify the destinations to which you want traffic to be directed. Using iRules, you can send traffic not only to pools, but also to individual pool members, ports, or URIs. The iRules you create can be simple or sophisticated, depending on your content-switching needs.

Events

iRules are event-driven, which means that the LTM system triggers an iRule based on an event that you specify in the iRule. An event declaration is the specification of an event within an iRule that causes the LTM system to trigger that iRule whenever that event occurs.

In a basic system configuration where no iRule exists, Local Traffic Manager directs incoming traffic to the default pool assigned to the virtual server that receives that traffic. However, you might want Local Traffic Manager to direct certain kinds of connections to other destinations. The way to do this is to write an iRule that directs traffic to that other destination, contingent on a certain type of event occurring. Otherwise, traffic continues to go to the default pool assigned to the virtual server.

iRules are therefore evaluated whenever an event occurs that you have specified in the iRule. For example, if an iRule includes the event declaration CLIENT_ACCEPTED, then the iRule is triggered whenever Local Traffic Manager accepts a client connection. Local Traffic Manager then follows the directions in the remainder of the iRule to determine the destination of the packet.

when CLIENT\_ACCEPTED {

if { [IP::addr [IP::client\_addr] equals 10.10.10.10] } {

pool my\_pool

}

}

This iRule is triggered when a client-side connection has been accepted, causing Local Traffic Manager to send the packet to the pool my_pool, if the client’s address matches 10.10.10.10.

For a full list of possible events see the following link:

https://devcentral.f5.com/wiki/irules.Events.ashx

2.01 - Given a specific iRule event determine what commands are available

https://support.f5.com/kb/en-us/products/big-ip_ltm/manuals/product/ltm-concepts-11-5-0/18.html

iRule Commands

An iRule command within an iRule causes Local Traffic Manager to take some action, such as querying for data, manipulating data, or specifying a traffic destination. The types of commands that you can include within iRules are:

Statement commands

These commands cause actions such as selecting a traffic destination or assigning a SNAT translation address. An example of a statement command is pool <name>, which directs traffic to the named load balancing pool.

Commands that query or manipulate data

Some commands search for header and content data, while others perform data manipulation such as inserting headers into HTTP requests. An example of a query command is IP::remote_addr, which searches for and returns the remote IP address of a connection. An example of a data manipulation command is HTTP::header remove <name>, which removes the last occurrence of the named header from a request or response.

Utility commands

These commands are functions that are useful for parsing and manipulating content. An example of a utility command is decode_uri <string>, which decodes the named string using HTTP URI encoding and returns the result.

For a full list of possible commands see the following link:

https://devcentral.f5.com/wiki/iRules.Commands.ashx

Objective - 2.02 Explain the functionality of a given iRule¶

2.02 - Interpret information in iRule logs to determine the iRule and iRule events where they occurred

https://devcentral.f5.com/articles/irules-101-09-debugging

Logging with iRules

The first tool you will want to arm yourself with is the iRules “log” command. The syntax for the log is

log [<facility>.<level>] <message>

facility : "local0", "local1", "local2", "local3", "local4", "local5",

"local6", "local7"

level: "alert", "crit", "debug", "emerg", "err", "error", "info",

"none", "notice", "panic", "warn", "warning"

While the facility and level parameters are optional, it is good to know that there is a significant behavioral difference when the optional <facility>.<level> is specified. When iRule logs messages without the facility and/or level, they are rate-limited as a class and subsequently logged messages within the rate-limit period may be suppressed even though they are textually different. However, when the <facility> and/or <level> are specified, the log messages are not rate-limited (though syslog-ng will still perform suppression of repeated duplicates).

Whew, that’s a lot of options. Lucky for you all that unless you are doing some customization in syslog-ng regarding the different facilities and levels, you can stick with the defaults of “local0” and “error” which are the defaults. Actually, we’ve made it even easier than that for you, in that you can omit the level parameter and we’ll default it for you. In almost every iRule you will see on DevCentral, the following syntax is used and in 99% of the cases, it will be all that you need.

log local0. "message goes here"

This will ensure that the log messages are not rate limited and go directly to the log files and that they will be stored in the system log file: /var/log/ltm.

A practical example

What and what not to log really depends on your iRule and what you are trying to accomplish with it. If you are trying to process a HTTP request, it’s probably a good idea to log the inputs to your iRule such as HTTP::host and HTTP::uri, as well as any temporary variables you are using if processing those string values. Let’s look at the following iRule.

when HTTP\_REQUEST {

switch -glob [HTTP::uri] {

"/app1\*" {

pool app1\_pool

}

"\*.gif" -

"\*.jpg" {

pool images\_pool

}

default {

pool def\_pool

}

}

}

This seems fairly straight forward. All requests to the “/app1” application will be sent to the app1_pool pool, all files with the “.gif” and “.jpg” extensions will be routed to the images_pool pool, and all other requests will be sent to the def_pool pool. Then you go to test your application and none of the images for the app1 application are being displayed. The way to go about debugging this issue would be to log the inputs and log the decision elements of the iRules logic to determine the source of the problem.

Your first thought is to go to the webserver logs for the image servers and see why the requests are not being honored. To your surpise, the logs show no requests on the image servers. Your next obvious step is to put some debugging in your iRule to see exactly what’s going on.

when HTTP\_REQUEST {

log local0. "Request: [HTTP::uri]"

switch -glob [HTTP::uri] {

"/app1\*" {

log local0. "Sending request to app1\_pool"

pool app1\_pool

}

"\*.gif" -

"\*.jpg" {

log local0. "Sending request to images\_pool"

pool images\_pool

}

default {

log local0. "Sending request to def\_pool"

pool def\_pool

}

}

}

Then when you run your traffic, you will see something like this in the logs

Request: /app1/index.html

Sending request to app1\_pool

Request: /js/file.js

Sending request to def\_pool

Request: /app1/smile.gif

Sending request to app1\_pool

What! I thought all image files were supposed to be sent to the images_pool pool but they are being sent to the app1_pool pool. Since the condition of searching for “/app1” was before the “gif/”jpg” test, it matched and requests were sent to the app1_pool pool of servers. Now that you have this information, it’s fairly easy to reorder the conditions in the switch statement to ensure all image request go to the images_pool pool.

when HTTP\_REQUEST {

log local0. "Request: [HTTP::uri]"

switch -glob [HTTP::uri] {

"\*.gif" -

"\*.jpg" {

log local0. "Sending request to images\_pool"

pool images\_pool

}

"/app1\*" {

log local0. "Sending request to app1\_pool"

pool app1\_pool

}

default {

log local0. "Sending request to def\_pool"

pool def\_pool

}

}

}

Now to your pleasure, the images are displaying in your application. Just for kicks you look at the logs and see something like the following:

Request: /app1/index.html

Sending request to app1\_pool

Request: /js/file.js

Sending request to def\_pool

Request: /app1/smile.gif

Sending request to images\_poo

All is good, the app is working, and all images are being displayed properly. You’re done right? WRONG…

Remove Logging in Production

Debug logging is a great tool when testing your application deployments, or even when fixing an issue with production servers. But, log messages do fill up the system logs and the system disks are only so big. In most cases, debug logging should be disabled when you’ve got all the kinks worked out. This can be done in several ways:

Remove the log commands from the iRule. This is probably the easiest to implement, just delete the log lines and click save. This option will reduce the clutter in your iRule and makes it easier to read.

Comment out the log commands with a # sign. This will enable you to easily restore the log commands if another situation comes up where you need to figure out a new app error. Just uncomment the log lines, click save, and you are back in business.

Use conditional log statements based on global variables. By wrapping log statements with an if statement testing the value of a variable, you can make turning on and off logging as simple as changing a variable. The above iRule could be written like this.

when HTTP\_REQUEST { set DEBUG 1 if { $DEBUG } { log local0. "Request: [HTTP::uri]" } switch -glob [HTTP::uri] { "\*.gif" - "\*.jpg" { if { $DEBUG } { log local0. "Sending request to images\_pool" } pool images\_pool } "/app1\*" { if { $DEBUG } { log local0. "Sending request to app1\_pool" } pool app1\_pool } default { if { $DEBUG } { log local0. "Sending request to def\_pool" } pool def\_pool } } }

Then by setting DEBUG to 1 will enable logging and setting it to 0 will turn logging off. The method you use will solely depend on your own situation. Options 1 and 2 take no CPU overhead in the log processing, while option 3 still requires performing a Boolean test on a variable. For hundreds of thousands of requests, this can add up.

Wrapping it up¶

First thing to know and imprint in your mind is that logging is your friend. You should get in the habit of including some form of logging in all new iRule development to speed up diagnosing issues. Just make sure that you remember to disable those log commands when you move your iRule into production so that you keep from filling up the BIG-IP’s filesystem.

For more information on the log command see the following link:

https://devcentral.f5.com/wiki/iRules.log.ashx

2.02 - Describe the results of iRule errors

https://support.f5.com/kb/en-us/solutions/public/13000/900/sol13905.html?sr=46137011

iRule Errors

When an iRule contains an error, such as a missing variable, the system generates a TCL error indicating the missing or incorrect element. A TCL runtime error aborts the affected instance of the iRule, and may cause the associated connection to be reset. The error message can provide valuable information when creating and troubleshooting iRule syntax.

If the error message occurs during operation or while creating an iRule, use the information in the error message to troubleshoot the iRule syntax. If the error occurs after upgrading the BIG-IP system to a new software release, refer to the DevCentral site and verify whether any portion of the iRule syntax (such as an iRule command) was deprecated or changed.

Error Message

*Error Message: 01220001:3: TCL error*

For example:

*01220001:3: TCL error: /Common/broken <RULE\_INIT> - can't read "b": no

such variable while executing "set a $b"*

*01220001:3: TCL error: MyiRule <HTTP\_RESPONSE> - wrong # args: should

be ""persist add uie <key>" while executing "persist add uie

[HTTP::cookie "cookie\_name"]" *

*01220001:3: TCL error: MyiRule - Out of bounds (line 2) invoked from

within "HTTP::payload replace 0 $content\_length [string repeat "X"

$content\_length]"*

Objective - 2.03 Given specific traffic and configuration containing a simple iRule determine the result of the iRule on the traffic¶

2.03 - Use an iRule to resolve application issues related to traffic steering and/or application data

https://devcentral.f5.com/articles/routing-traffic-by-uri-using-irule

Routing traffic by URI using iRule

DevCentral has a good article on this topic as an example.

The Challenge:

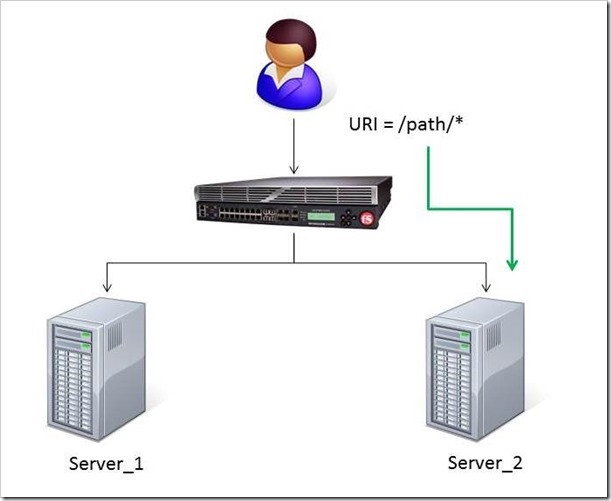

When a user conducts a search on a website and is directed to one of the servers, the search information is cached on that server. If another user searches for that same data but the LTM load balances to the other server, the cached data from the first server does him no good. So to solve this caching problem, the customer wants traffic that contains a specific search parameter to be routed to the second server (as long as the server is available). Specifically in this case, when a user loads a page and the URI starts with /path/* that traffic should be sent to Server_2.

The picture below shows a representation of what the customer wants to accomplish:

The Solution:

So, the question becomes: How does the customer ensure all /path/* traffic is sent to a specific server? Well, you guessed it…the ubiquitous and loveable iRule! Everyone had a pretty good idea an iRule would be used to solve this problem, but what does that iRule look like? Well, here it is!!

when HTTP\_REQUEST {

if { [string tolower [HTTP::path]] starts\_with "/path/" } {

persist none

set pm [lsearch -inline [active\_members -list <pool name>]

x.x.x.x\*]

catch { pool <pool name> member [lindex $pm 0] [lindex $pm 1] }

}

}

Let’s talk through the specifics of this solution…

For efficiency, start by checking the least likely condition. If an HTTP_REQUEST comes in, immediately check for the “/path/” string. Keep in mind the “string tolower” command on the HTTP::path before the comparison to “/path/” to ensure the cases match correctly. Also, notice the use of HTTP::path instead of the full URI for the comparison…there’s no need to use the full URI for this check.

Next, turn off persistence just in case another profile or iRule is forcing the connection to persist to a place other than the beloved Server_2.

Then, search all active members in the pool for the Server_2 IP address and port. The “lsearch -inline” ensures the matching value is returned instead of just the index. The “active_members -list” is used to ensure we get a list of IP addresses and ports, not just the number of active members. Note the asterisk behind the IP address in the search command…this is needed to ensure the port number is included in the search. Based on the searches, the resulting values are set in a variable called “pm”.

Next, use the catch command to stop any TCL errors from causing problems. Because we are getting the active members list, it’s possible that the pool member we are trying to match is NOT active and therefore the pool member listed in the pool command may not be there…this is what might cause that TCL error. Then send the traffic to the correct pool member, which requires the IP and port. The astute observer and especially the one familiar with the output of “active_members -list” will notice that each pool member returned in the list is already pre-formatted in “ip port” format. However, just using the pm variable in the pool command returns a TCL error, likely because the pm variable is a single object instead of two unique objects. So, the lindex is used to pull out each element individually to avoid the TCL error.

Testing:

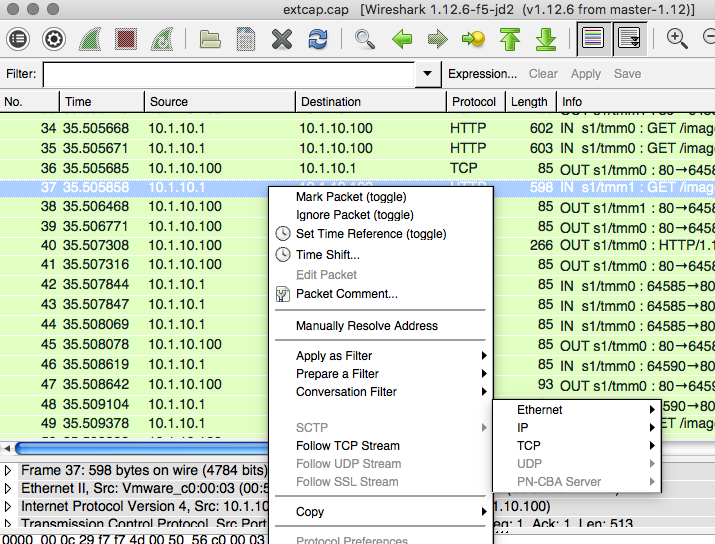

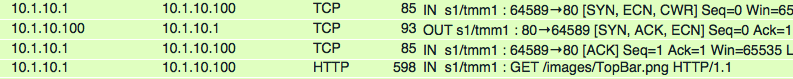

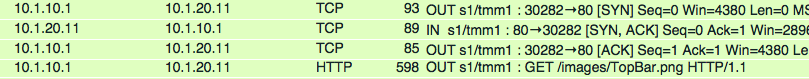

Our team tested the iRule by adding it to a development site and then accessing several pages on that site. We made sure the pages included “/path/” in the URIs! We used tcpdump on the BIG-IP to capture the transactions (tcpdump -ni 0.0 -w/var/tmp/capture1.pcap tcp port 80 -s0) and then downloaded them locally and used Wireshark for analysis. Using these tools, we determined that all the “/path/” traffic routed to Server_2 and all other traffic was still balanced between Server_1 and Server_2. So, the iRule worked correctly and it was ready for prime time!

Special thanks to Jason Rahm and Joe Pruitt for their outstanding technical expertise and support in solving this challenge!

Objective - 2.04 Interpret AVR information to identify performance issues or application attacks¶

2.04 - Explain how to modify profile settings using information from the AVR

Changing the default values in the Analytics profile

Reported information that is captured by AVR can be used to help you understand what is happening with the application and possible tune settings in the BIG-IP configuration.

You may have users experiencing slow Page Load Times which is the length of time it takes for application web pages to load on client-side browsers. This information is useful if end users report that an application is slow, and you want to determine the cause of the problem. Adjusting the TCP profile to account for Cell or WAN based users on the client side may help improve the issue or understanding that the content is large and perhaps doing some simple compression may help the user experience.

2.04 - Explain how to use advanced filters to narrow output data from AVR

You can review charts that show statistical information about traffic to your web applications. The charts provide visibility into application behavior, user experience, transactions, and data center resource usage.

On the Main tab, click Statistics > Analytics > HTTP. The Overview screen opens.

From the Override time range to list, select a new time frame to apply to all of the widgets in the overview.

Tip: Within each widget you can override the default time range, as needed.

For each widget, select the data format and the time range to display, as needed.

From the menu bar, select the type of statistics you want to view.

Select this option To see these application statistics Overview Top statistical information about traffic on your system or managed systems, such as the top virtual servers, top URLs accessed, and top applications. You can customize the information that is displayed. Transactions The HTTP transaction rate (transactions per second) passing through the web applications, and the number of transactions to and from the web applications. Latency > Server Latency The number of milliseconds it takes from the time a request arrives at the virtual server until a response arrives at the virtual server. Latency > Page Load Time The number of milliseconds it takes for a web page to fully load on a client browser, from the time the user clicks a link or enters a web address until the web page displays in its entirety. Throughput > Request Throughput HTTP request throughput in bits per second. Throughput > Response Throughput HTTP response throughput in bits per second. Sessions > New Sessions The number of transactions that open new sessions, in sessions per second. Sessions > Concurrent Sessions The total number of open and active sessions at a given time, until they time out. The charts display information based on the settings you enabled in the Analytics profile.

From the View By list, select the specific network object type for which you want to display statistics. You can also click Expand Advanced Filters to filter the information that displays.

To focus in on the specific details you want more information about, click the chart or the details. The system refreshes the charts and displays information about the item.

On the screen, the system displays the path you followed to reach the current display, including the items you clicked. For example, to review throughput details for a particular virtual server, follow these steps:

From the Throughput menu, choose Request Throughput.

From the View By list, select Virtual Servers. The charts show throughput statistics for all virtual servers on this BIG-IP system. You can point on the charts to display specific numbers.

Click the virtual server you want more information about. You can either click a part of the pie chart or click the name of the virtual server in the Details table. The charts show throughput statistics for that virtual server, and shows the path you used to display the information.

To view information about other applications or retrace your path, click a link (in blue) in the path displayed by the charts.

As you drill down into the statistics, you can locate more details and view information about a specific item on the charts.

You can continue to review the collected metrics on the system viewing transactions, latency, throughput, and sessions. As a result, you become more familiar with the system, applications, resource utilization, and more, and you can view the statistics in clear graphical charts, and troubleshoot the system as needed.

2.04 - Identify potential latency increases within an application

Investigating the server latency of applications

You can review statistics concerning server latency on the Analytics charts. Server latency is how long it takes (in milliseconds) from the time a request reaches the BIG-IP system, for it to proceed to the web application server, and return a response to the BIG-IP system.

- On the Main tab, click Statistics > Analytics > HTTP. The Overview screen opens.

- From the Latency menu, choose Server Latency. A chart shows the server latency for all applications and virtual servers associated with all Analytics profiles.

- To view server latency for a specific application, in the Details table, select only that application. The charts show latency only for the selected application.

- To view server latency for a specific virtual server:

- In the View By list, select Virtual Servers. The charts show latency for all virtual servers.

- In the Details list near the charts, click the virtual server you are interested in. The charts show latency only for the selected virtual server.

- If further investigation is needed, in the View By setting, select other entities to view charts that show latency for other collected entities included in the Analytics profile, for example, specific pool members, URLs, countries, or client IP addresses.

Tip: If you are concerned about server latency, you can configure the Analytics profile so that it sends an alert when the average server latency exceeds a number of milliseconds for some period of time.

Objective - 2.05 Interpret AVR information to identify LTM device misconfiguration¶

2.05 - Explain how to use AVR to trace application traffic

AVR to trace application traffic

This implementation describes how to set up the BIG-IP system to collect application traffic so that you can troubleshoot problems that have become apparent by monitoring application statistics. For example, by examining captured requests and responses, you can investigate issues with latency, throughput, or reduced transactions per second to understand what is affecting application performance.

When Application Visibility and Reporting (AVR) is provisioned, you can create an Analytics profile that includes traffic capturing instructions. The system can collect application traffic locally, remotely, or both. If the system is already monitoring applications, you can also update an existing Analytics profile to make it so that it captures traffic.

If logging locally, the system logs the first 1000 transactions and displays charts based on the analysis of those transactions. If logging remotely, the system logs information on that system; log size is limited only by any constraints of the remote logging system. To see updated application statistics, you can clear the existing data to display the current statistics.

Prerequisites for capturing application traffic

After you finish a basic networking configuration of the BIG-IP system, you must complete the following tasks as prerequisites for setting up application statistics collection:

- Provision Application Visibility and Reporting (AVR): System > Resource Provisioning

- Create an iAppsTM application service (go to iApp > Application Services), or configure at least one virtual server with a pool pointing to one or more application servers.

- The Traffic Sampling Ratio must be set to all in the default Analytics profile.

You can set up the system for capturing traffic locally or remotely (or both).

Tip: Before setting up traffic capturing, it is a good idea to clear the captured transaction log. On the Captured Transactions screen, click Clear All to clear all previously captured data records.

Capturing traffic for troubleshooting

To set up traffic capturing, the Transaction Sampling Ratio of the default analytics profile must be set to All.

You can configure the BIG-IP system to capture application traffic and store the information locally or remotely (on syslog servers or SIEM devices, such as Splunk). To do this, you create an Analytics profile designed for capturing traffic. The profile instructs the BIG-IP system to collect a portion of application traffic using the Application Visibility and Reporting module.

Note: You typically use traffic capturing if you notice an application issue, such as trouble with throughput or latency, discovered when examining application statistics, and want to troubleshoot the system by examining actual transactions.

On the Main tab, click Local Traffic > Profiles > Analytics.

Tip: If Analytics is not listed, this indicates that Application Visibility and Reporting (AVR) is not provisioned, or you do not have rights to create profiles.

The Analytics screen opens and lists all Analytics profiles that are on the system, including a default profile called analytics.

Click Create.

The New Analytics Profile screen opens. By default, the settings are initially the same as in the default analytics profile.

In the Profile Name field, type a name for the Analytics profile.

To the right of the General Configuration area, click the Custom check box.

The settings in the area become available for modification.

For Traffic Capturing Logging Type, specify where to store captured traffic.

- To store traffic locally, click Internal. You can view details on the Statistics: Captured Transactions screen. This option is selected by default.

- To store traffic on a remote logging server, click External and type the Remote Server IP Address and Remote Server Port number.

Tip: If you specify remote logging for multiple applications, you can use the Remote Server Facility filter to sort the data for each.

In the Included Objects area, specify the virtual servers for which to capture application statistics:

For the Virtual Servers setting, click Add.

A popup lists the virtual servers that you can assign to the Analytics profile.

From the Select Virtual Server popup list, select the virtual servers to include and click Done.

Note: You need to have previously configured the virtual servers (with an HTTP profile) for them to appear in the list. Also, you can assign only one Analytics profile to a virtual server so the list shows only virtual servers that have not been assigned an Analytics profile.

Special considerations apply if using Analytics on a BIG-IP system with both Application Security ManagerTM and Access Policy ManagerTM, where security settings (in Portal Access WebTop or an iRule) redirect traffic from one virtual server to a second one. In this case, you need to attach the Analytics profile to the second virtual server to ensure that the charts show accurate statistics.

In the Statistics Gathering Configuration, for Collected Metrics, select the statistics you want the system to collect:

Option Description Server Latency Tracks how long it takes to get data from the application server to the BIG-IP system (selected by default). Page Load Time Tracks how long it takes an application user to get a complete response from the application, including network latency and completed page processing.

Note: End user response times and latencies can vary significantly based on geography and connection types.

Throughput Saves information about HTTP request and response throughput (selected by default). User Sessions Stores the number of unique user sessions. For Timeout, type the number of minutes of user non-activity to allow before the system considers the session to be over. If using transaction sampling, this option is not available. For Collected Entities, select the entities for which you want the system to collect statistics:

Option Description URLs Collects the requested URLs. Countries Saves the name of the country where the request came from based on the client IP address. Client IP Addresses Saves the IP address where the request originated. The address saved also depends on whether the request has an XFF (X-forwarded-for) header and whether Trust XFF is selected. Response Codes Saves HTTP response codes that the server returned to requesters (selected by default). User Agents Saves information about browsers used when making the request. Methods Saves HTTP methods in requests (selected by default). In the Capture Filter area, from the Capture Requests and Capture Responses lists, select the options that indicate the part of the traffic to capture.

Option Description None Specifies that the system does not capture request (or response) data. Headers Specifies that the system captures request (or response) header data only. Body Specifies that the system captures the body of requests (or responses) only. All Specifies that the system captures all request (or response) data. Depending on the application, customize the remaining filter settings to capture the portion of traffic to that you need for troubleshooting.

Tip: By focusing in on the data and limiting the type of information that is captured, you can troubleshoot particular areas of an application more quickly. For example, capture only requests or responses, specific status codes or methods, or headers containing a specific string.

Click Finished.

The BIG-IP system captures the application traffic described by the Analytics profile for 1000 transactions locally (or until system limits are reached). If logging remotely, the system logs information on that system; log size is limited only by constraints of the remote logging system.

Note: System performance is affected when traffic is being captured.

Reviewing captured traffic

Before you can review captured traffic details on the BIG-IP system, you need to have created an Analytics profile that is capturing application traffic locally. The settings you enable in the Capture Filter area of the profile determine what information the system captures. You need to associate the Analytics profile with one or more virtual servers, or with an iApps application service.

The system starts capturing application traffic as soon as you enable it on the Analytics profile. You can review the captured transactions locally on the BIG-IP system. The system logs the first 1000 transactions.

On the Main tab, click System > Logs > Captured Transactions.

The Captured Transactions screen opens and lists all of the captured transactions.

Optionally, use the time period and filter settings to limit which transactions are listed.

In the Captured Traffic area, click any transaction that you want to examine.

Details of the request will display on the screen.

Review the general details of the request.

Tip: The general details, such as the response code or the size of the request and response, help with troubleshooting.

For more information, click Request or Response to view the contents of the actual transaction. Review the data for anything unexpected, and other details that will help with troubleshooting the application.

On the Captured Transactions screen, click Clear All to clear all previously captured data records (including those not displayed on the screen) and start collecting transactions again.

The system captures up to 1000 transactions locally and displays them on the screen. Captured transactions are visible a few seconds after they occur.

2.05 - Explain how latency trends identify application tier bottlenecks

Latency is a classic network performance metric, which at the basic level requires the evaluation of timestamps applied to the same packet as it passes through two locations in the network. By comparing the timestamps, the latency of the network segment can be monitored. Many networked applications and services rely on low latency in order to function correctly.

If you have established latency times for transport traffic in your network and you are seeing latency grow or exceed a threshold that causes user acceptance to drop for an application, you can use it as a basis to look into changes or setting that may be causing additional latency. Gathering the information and keep track of changes is the key to identifying application tier issues.

Investigating the server latency of applications

Before you can investigate server latency, you need to have created an Analytics profile that is logging statistics internally on the BIG-IP system. The Analytics profile must be associated with one or more virtual servers, or an iApps application service. If your browser is IE8 or earlier, you need to have Adobe Flash Player installed on the computer from which you plan to review the data.

Note: Newer browsers (Internet Explorer 9 or later, Firefox 3.6 or later, or Chrome 14 or later) support viewing Analytics charts with no additional plug-in. If using older browsers (Internet Explorer 8 or earlier, Firefox 3.5 or earlier, or Chrome 13 or earlier), Adobe Flash Player (version 8 or later) must be installed on the computer where you plan to view Analytics charts.

You can review statistics concerning server latency on the Analytics charts. Server latency is how long it takes (in milliseconds) from the time a request reaches the BIG-IP system, for it to proceed to the web application server, and return a response to the BIG-IP system.

- On the Main tab, click Statistics > Analytics > HTTP. The Overview screen opens.

- From the Latency menu, click Server Latency. A chart shows the server latency for all applications and virtual servers associated with all Analytics profiles.

- To view server latency for a specific application, in the Details table, select only that application. The charts show latency only for the selected application.

- To view server latency for a specific virtual server:

- In the View By list, select Virtual Servers. The charts show latency for all virtual servers.

- In the Details list near the charts, click the virtual server you are interested in. The charts show latency only for the selected virtual server.

- If further investigation is needed, in the View By setting, select other entities to view charts that show latency for other collected entities included in the Analytics profile, for example, specific pool members, URLs, countries, or client IP addresses.

Tip: If you are concerned about server latency, you can configure the Analytics profile so that it sends an alert when the average server latency exceeds a number of milliseconds for some period of time.

Objective - 2.06 Given a set of headers or traces, determine the root cause of an HTTP/HTTPS application problem¶

2.06 - Explain how to interpret response codes

http://www.w3.org/Protocols/rfc2616/rfc2616-sec10.html

Response Codes

The Status-Code element is a 3-digit integer result code of the attempt to understand and satisfy the request. The Reason-Phrase is intended to give a short textual description of the Status-Code. The Status-Code is intended for use by automata and the Reason-Phrase is intended for the human user. The client is not required to examine or display the Reason- Phrase.

The first digit of the Status-Code defines the class of response. The last two digits do not have any categorization role. There are 5 values for the first digit:

- 1xx: Informational - Request received, continuing process

- 2xx: Success - The action was successfully received, understood, and accepted

- 3xx: Redirection - Further action must be taken in order to complete the request

- 4xx: Client Error - The request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled

- 5xx: Server Error - The server failed to fulfill an apparently valid request

Status Code Definitions

Each Status-Code is described below, including a description of which method(s) it can follow and any meta information required in the response.

Informational 1xx

This class of status code indicates a provisional response, consisting only of the Status-Line and optional headers, and is terminated by an empty line. There are no required headers for this class of status code. Since HTTP/1.0 did not define any 1xx status codes, servers must not send a 1xx response to an HTTP/1.0 client except under experimental conditions.

A client must be prepared to accept one or more 1xx status responses prior to a regular response, even if the client does not expect a 100 (Continue) status message. A user agent MAY ignore an unexpected 1xx status response.

Proxies must forward 1xx responses, unless the connection between the proxy and its client has been closed, or unless the proxy itself requested the generation of the 1xx response. (For example, if a proxy adds a “Expect: 100-continue” field when it forwards a request, then it need not forward the corresponding 100 (Continue) response(s).)

100 Continue

The client should continue with its request. This interim response is used to inform the client that the initial part of the request has been received and has not yet been rejected by the server. The client should continue by sending the remainder of the request or, if the request has already been completed, ignore this response. The server must send a final response after the request has been completed.

101 Switching Protocols

The server understands and is willing to comply with the client’s request, via the Upgrade message header field, for a change in the application protocol being used on this connection. The server will switch protocols to those defined by the response’s Upgrade header field immediately after the empty line, which terminates the 101 response.

The protocol should be switched only when it is advantageous to do so. For example, switching to a newer version of HTTP is advantageous over older versions, and switching to a real-time, synchronous protocol might be advantageous when delivering resources that use such features.

Successful 2xx

This class of status code indicates that the client’s request was successfully received, understood, and accepted.

200 OK

The request has succeeded. The information returned with the response is dependent on the method used in the request, for example:

GET an entity corresponding to the requested resource is sent in the response;

HEAD the entity-header fields corresponding to the requested resource are sent in the response without any message-body;

POST an entity describing or containing the result of the action;

TRACE an entity containing the request message as received by the end server.

201 Created

The request has been fulfilled and resulted in a new resource being created. The newly created resource can be referenced by the URI(s) returned in the entity of the response, with the most specific URI for the resource given by a Location header field. The response should include an entity containing a list of resource characteristics and location(s) from which the user or user agent can choose the one most appropriate. The media type given in the Content-Type header field specifies the entity format. The origin server must create the resource before returning the 201 status code. If the action cannot be carried out immediately, the server should respond with 202 (Accepted) response instead.

A 201 response may contain an ETag response header field indicating the current value of the entity tag for the requested variant just created.

202 Accepted

The request has been accepted for processing, but the processing has not been completed. The request might or might not eventually be acted upon, as it might be disallowed when processing actually takes place. There is no facility for re-sending a status code from an asynchronous operation such as this.

The 202 response is intentionally non-committal. Its purpose is to allow a server to accept a request for some other process (perhaps a batch-oriented process that is only run once per day) without requiring that the user agent’s connection to the server persist until the process is completed. The entity returned with this response should include an indication of the request’s current status and either a pointer to a status monitor or some estimate of when the user can expect the request to be fulfilled.

203 Non-Authoritative Information

The returned metainformation in the entity-header is not the definitive set as available from the origin server, but is gathered from a local or a third-party copy. The set presented may be a subset or superset of the original version. For example, including local annotation information about the resource might result in a superset of the metainformation known by the origin server. Use of this response code is not required and is only appropriate when the response would otherwise be 200 (OK).

204 No Content

The server has fulfilled the request but does not need to return an entity-body, and might want to return updated metainformation. The response may include new or updated metainformation in the form of entity-headers, which if present should be associated with the requested variant.

If the client is a user agent, it should not change its document view from that which caused the request to be sent. This response is primarily intended to allow input for actions to take place without causing a change to the user agent’s active document view, although any new or updated metainformation should be applied to the document currently in the user agent’s active view.

The 204 response must not include a message-body, and thus is always terminated by the first empty line after the header fields.

205 Reset Content

The server has fulfilled the request and the user agent should reset the document view, which caused the request to be sent. This response is primarily intended to allow input for actions to take place via user input, followed by a clearing of the form in which the input is given so that the user can easily initiate another input action. The response must not include an entity.

206 Partial Content

The server has fulfilled the partial GET request for the resource. The request must have included a Range header field indicating the desired range, and may have included an If-Range header field to make the request conditional.

The response must include the following header fields:

- Either a Content-Range header field indicating the range included with this response, or a multipart/byteranges Content-Type including Content-Range fields for each part. If a Content-Length header field is present in the response, its value must match the actual number of OCTETs transmitted in the message-body.

- Date

- ETag and/or Content-Location, if the header would have been sent in a 200 response to the same request

- Expires, Cache-Control, and/or Vary, if the field-value might differ from that sent in any previous response for the same variant

If the 206 response is the result of an If-Range request that used a strong cache validator, the response should not include other entity-headers. If the response is the result of an If-Range request that used a weak validator, the response must not include other entity-headers; this prevents inconsistencies between cached entity-bodies and updated headers. Otherwise, the response must include all of the entity-headers that would have been returned with a 200 (OK) response to the same request.

A cache must not combine a 206 response with other previously cached content if the ETag or Last-Modified headers do not match exactly.

A cache that does not support the Range and Content-Range headers must not cache 206 (Partial) responses.

Redirection 3xx

This class of status code indicates that further action needs to be taken by the user agent in order to fulfill the request. The user agent may carry out the action required without interaction with the user if and only if the method used in the second request is GET or HEAD. A client should detect infinite redirection loops, since such loops generate network traffic for each redirection.

Note: previous versions of this specification recommended a maximum of five redirections. Content developers should be aware that there might be clients that implement such a fixed limitation.

300 Multiple Choices

The requested resource corresponds to any one of a set of representations, each with its own specific location, and agent- driven negotiation information is being provided so that the user (or user agent) can select a preferred representation and redirect its request to that location.

Unless it was a HEAD request, the response should include an entity containing a list of resource characteristics and location(s) from which the user or user agent can choose the one most appropriate. The media type given in the Content-Type header field specifies the entity format. Depending upon the format and the capabilities of the user agent, selection of the most appropriate choice may be performed automatically. However, this specification does not define any standard for such automatic selection.

If the server has a preferred choice of representation, it should include the specific URI for that representation in the Location field; user agents may use the Location field value for automatic redirection. This response is cacheable unless indicated otherwise.

301 Moved Permanently

The requested resource has been assigned a new permanent URI and any future references to this resource should use one of the returned URIs. Clients with link editing capabilities ought to automatically re-link references to the Request-URI to one or more of the new references returned by the server, where possible. This response is cacheable unless indicated otherwise.

The Location field in the response should give the new permanent URI. Unless the request method was HEAD, the entity of the response should contain a short hypertext note with a hyperlink to the new URI(s).

If the 301 status code is received in response to a request other than GET or HEAD, the user agent must not automatically redirect the request unless it can be confirmed by the user, since this might change the conditions under which the request was issued.

Note: When automatically redirecting a POST request after receiving a 301 status code, some existing HTTP/1.0 user agents will erroneously change it into a GET request.

302 Found

The requested resource resides temporarily under a different URI. Since the redirection might be altered on occasion, the client should continue to use the Request-URI for future requests. This response is only cacheable if indicated by a Cache-Control or Expires header field.

The temporary URI should be given by the Location field in the response. Unless the request method was HEAD, the entity of the response should contain a short hypertext note with a hyperlink to the new URI(s).

If the 302 status code is received in response to a request other than GET or HEAD, the user agent must not automatically redirect the request unless it can be confirmed by the user, since this might change the conditions under which the request was issued.

Note: RFC 1945 and RFC 2068 specify that the client is not allowed to change the method on the redirected request. However, most existing user agent implementations treat 302 as if it were a 303 response, performing a GET on the Location field-value regardless of the original request method. The status codes 303 and 307 have been added for servers that wish to make unambiguously clear which kind of reaction is expected of the client.

303 See Other

The response to the request can be found under a different URI and should be retrieved using a GET method on that resource. This method exists primarily to allow the output of a POST-activated script to redirect the user agent to a selected resource. The new URI is not a substitute reference for the originally requested resource. The 303 response must not be cached, but the response to the second (redirected) request might be cacheable.

The Location field in the response should give the different URI. Unless the request method was HEAD, the entity of the response should contain a short hypertext note with a hyperlink to the new URI(s).

Note: Many pre-HTTP/1.1 user agents do not understand the 303 status. When interoperability with such clients is a concern, the 302 status code may be used instead, since most user agents react to a 302 response as described here for 303.

304 Not Modified

If the client has performed a conditional GET request and access is allowed, but the document has not been modified, the server should respond with this status code. The 304 response must not contain a message-body, and thus is always terminated by the first empty line after the header fields.

The response must include the following header fields:

Date, unless its omission is required

If a clockless origin server obeys these rules, and proxies and clients add their own Date to any response received without one (as already specified by RFC 2068), caches will operate correctly.

ETag and/or Content-Location, if the header would have been sent in a 200 response to the same request

Expires, Cache-Control, and/or Vary, if the field-value might differ from that sent in any previous response for the same variant

If the conditional GET used a strong cache validator, the response should not include other entity-headers. Otherwise (i.e., the conditional GET used a weak validator), the response must not include other entity-headers; this prevents inconsistencies between cached entity-bodies and updated headers.

If a 304 response indicates an entity not currently cached, then the cache must disregard the response and repeat the request without the conditional.

If a cache uses a received 304 response to update a cache entry, the cache must update the entry to reflect any new field values given in the response.

305 Use Proxy

The requested resource must be accessed through the proxy given by the Location field. The Location field gives the URI of the proxy. The recipient is expected to repeat this single request via the proxy. 305 responses must only be generated by origin servers.

Note: RFC 2068 was not clear that 305 was intended to redirect a single request, and to be generated by origin servers only. Not observing these limitations has significant security consequences.

306 (Unused)

The 306 status code was used in a previous version of the specification, is no longer used, and the code is reserved.

307 Temporary Redirect

The requested resource resides temporarily under a different URI. Since the redirection may be altered on occasion, the client should continue to use the Request-URI for future requests. This response is only cacheable if indicated by a Cache-Control or Expires header field.

The temporary URI should be given by the Location field in the response. Unless the request method was HEAD, the entity of the response should contain a short hypertext note with a hyperlink to the new URI(s), since many pre-HTTP/1.1 user agents do not understand the 307 status. Therefore, the note should contain the information necessary for a user to repeat the original request on the new URI.

If the 307 status code is received in response to a request other than GET or HEAD, the user agent must not automatically redirect the request unless it can be confirmed by the user, since this might change the conditions under which the request was issued.

Client Error 4xx

The 4xx class of status code is intended for cases in which the client seems to have erred. Except when responding to a HEAD request, the server should include an entity containing an explanation of the error situation, and whether it is a temporary or permanent condition. These status codes are applicable to any request method. User agents should display any included entity to the user.

If the client is sending data, a server implementation using TCP should be careful to ensure that the client acknowledges receipt of the packet(s) containing the response, before the server closes the input connection. If the client continues sending data to the server after the close, the server’s TCP stack will send a reset packet to the client, which may erase the client’s unacknowledged input buffers before they can be read and interpreted by the HTTP application.

400 Bad Request

The server due to malformed syntax could not understand the request. The client should not repeat the request without modifications.

401 Unauthorized

The request requires user authentication. The response must include a WWW-Authenticate header field containing a challenge applicable to the requested resource. The client MAY repeat the request with a suitable Authorization header field. If the request already included Authorization credentials, then the 401 response indicates that authorization has been refused for those credentials. If the 401 response contains the same challenge as the prior response, and the user agent has already attempted authentication at least once, then the user should be presented the entity that was given in the response, since that entity might include relevant diagnostic information. HTTP access authentication is explained in “HTTP Authentication: Basic and Digest Access Authentication”.

402 Payment Required

This code is reserved for future use.

403 Forbidden

The server understood the request, but is refusing to fulfill it. Authorization will not help and the request should not be repeated. If the request method was not HEAD and the server wishes to make public why the request has not been fulfilled, it should describe the reason for the refusal in the entity. If the server does not wish to make this information available to the client, the status code 404 (Not Found) can be used instead.

404 Not Found

The server has not found anything matching the Request-URI. No indication is given of whether the condition is temporary or permanent. The 410 (Gone) status code should be used if the server knows, through some internally configurable mechanism, that an old resource is permanently unavailable and has no forwarding address. This status code is commonly used when the server does not wish to reveal exactly why the request has been refused, or when no other response is applicable.

405 Method Not Allowed

The method specified in the Request-Line is not allowed for the resource identified by the Request-URI. The response must include an Allow header containing a list of valid methods for the requested resource.

406 Not Acceptable

The resource identified by the request is only capable of generating response entities which have content characteristics not acceptable according to the accept headers sent in the request.

Unless it was a HEAD request, the response should include an entity containing a list of available entity characteristics and location(s) from which the user or user agent can choose the one most appropriate. The media type given in the Content-Type header field specifies the entity format. Depending upon the format and the capabilities of the user agent, selection of the most appropriate choice MAY be performed automatically. However, this specification does not define any standard for such automatic selection.

Note: HTTP/1.1 servers are allowed to return responses which are not acceptable according to the accept headers sent in the request. In some cases, this may even be preferable to sending a 406 response. User agents are encouraged to inspect the headers of an incoming response to determine if it is acceptable.

If the response could be unacceptable, a user agent should temporarily stop receipt of more data and query the user for a decision on further actions.

407 Proxy Authentication Required

This code is similar to 401 (Unauthorized), but indicates that the client must first authenticate itself with the proxy. The proxy must return a Proxy-Authenticate header field containing a challenge applicable to the proxy for the requested resource. The client may repeat the request with a suitable Proxy-Authorization header field. HTTP access authentication is explained in “HTTP Authentication: Basic and Digest Access Authentication”.

408 Request Timeout

The client did not produce a request within the time that the server was prepared to wait. The client may repeat the request without modifications at any later time.

409 Conflict

The request could not be completed due to a conflict with the current state of the resource. This code is only allowed in situations where it is expected that the user might be able to resolve the conflict and resubmit the request. The response body should include enough information for the user to recognize the source of the conflict. Ideally, the response entity would include enough information for the user or user agent to fix the problem; however, that might not be possible and is not required.

Conflicts are most likely to occur in response to a PUT request. For example, if versioning were being used and the entity being PUT included changes to a resource which conflict with those made by an earlier (third-party) request, the server might use the 409 response to indicate that it can’t complete the request. In this case, the response entity would likely contain a list of the differences between the two versions in a format defined by the response Content-Type.

410 Gone

The requested resource is no longer available at the server and no forwarding address is known. This condition is expected to be considered permanent. Clients with link editing capabilities should delete references to the Request-URI after user approval. If the server does not know, or has no facility to determine, whether or not the condition is permanent, the status code 404 (Not Found) should be used instead. This response is cacheable unless indicated otherwise.

The 410 response is primarily intended to assist the task of web maintenance by notifying the recipient that the resource is intentionally unavailable and that the server owners desire that remote links to that resource be removed. Such an event is common for limited-time, promotional services and for resources belonging to individuals no longer working at the server’s site. It is not necessary to mark all permanently unavailable resources as “gone” or to keep the mark for any length of time – that is left to the discretion of the server owner.

411 Length Required

The server refuses to accept the request without a defined Content- Length. The client may repeat the request if it adds a valid Content-Length header field containing the length of the message-body in the request message.

412 Precondition Failed

The precondition given in one or more of the request-header fields evaluated to false when it was tested on the server. This response code allows the client to place preconditions on the current resource metainformation (header field data) and thus prevent the requested method from being applied to a resource other than the one intended.

413 Request Entity Too Large

The server is refusing to process a request because the request entity is larger than the server is willing or able to process. The server may close the connection to prevent the client from continuing the request.

If the condition is temporary, the server should include a Retry-After header field to indicate that it is temporary and after what time the client may try again.

414 Request-URI Too Long

The server is refusing to service the request because the Request-URI is longer than the server is willing to interpret. This rare condition is only likely to occur when a client has improperly converted a POST request to a GET request with long query information, when the client has descended into a URI “black hole” of redirection (e.g., a redirected URI prefix that points to a suffix of itself), or when the server is under attack by a client attempting to exploit security holes present in some servers using fixed-length buffers for reading or manipulating the Request-URI.

415 Unsupported Media Type

The server is refusing to service the request because the entity of the request is in a format not supported by the requested resource for the requested method.

416 Requested Range Not Satisfiable

A server should return a response with this status code if a request included a Range request-header field, and none of the range-specifier values in this field overlap the current extent of the selected resource, and the request did not include an If-Range request-header field. (For byte-ranges, this means that the first- byte-pos of all of the byte-range-spec values were greater than the current length of the selected resource.)

When this status code is returned for a byte-range request, the response should include a Content-Range entity-header field specifying the current length of the selected resource. This response must not use the multipart/byteranges content- type.

417 Expectation Failed

This server could not meet the expectation given in an Expect request-header field, or, if the server is a proxy, the server has unambiguous evidence that the next-hop server could not meet the request.

Server Error 5xx

Response status codes beginning with the digit “5” indicate cases in which the server is aware that it has erred or is incapable of performing the request. Except when responding to a HEAD request, the server should include an entity containing an explanation of the error situation, and whether it is a temporary or permanent condition. User agents should display any included entity to the user. These response codes are applicable to any request method.

500 Internal Server Error

The server encountered an unexpected condition, which prevented it from fulfilling the request.

501 Not Implemented

The server does not support the functionality required to fulfill the request. This is the appropriate response when the server does not recognize the request method and is not capable of supporting it for any resource.

502 Bad Gateway

The server, while acting as a gateway or proxy, received an invalid response from the upstream server it accessed in attempting to fulfill the request.

503 Service Unavailable

The server is currently unable to handle the request due to a temporary overloading or maintenance of the server. The implication is that this is a temporary condition, which will be alleviated after some delay. If known, the length of the delay may be indicated in a Retry-After header. If no Retry-After is given, the client should handle the response as it would for a 500 response.

Note: The existence of the 503 status code does not imply that a server must use it when becoming overloaded. Some servers may wish to simply refuse the connection.

504 Gateway Timeout

The server, while acting as a gateway or proxy, did not receive a timely response from the upstream server specified by the URI (e.g. HTTP, FTP, LDAP) or some other auxiliary server (e.g. DNS) it needed to access in attempting to complete the request.

Note: Note to implementers: some deployed proxies are known to return 400 or 500 when DNS lookups time out.

505 HTTP Version Not Supported

The server does not support, or refuses to support, the HTTP protocol version that was used in the request message. The server is indicating that it is unable or unwilling to complete the request using the same major version as the client, as described in section 3.1, other than with this error message. The response should contain an entity describing why that version is not supported and what other protocols that server supports.

2.06 - Explain the function of HTTP headers within different HTTP applications (Cookies, Cache Control, Vary, Content Type & Host)

https://f5.com/resources/white-papers/fundamentals-of-http

HTTP Headers

HTTP headers carry information about behavior and application state between the browser and the server. These headers can be modified and examined by the browser and the server, as well as intermediary devices such as web acceleration solutions and application delivery controllers. The headers sent by the browser notify the web server of the browser’s capabilities. The headers sent by the web server tell the browser how to treat the content.

The most important browser headers, in terms of end-user performance, are:

- HTTP version (HTTP/1.0 or HTTP/1.1)

- Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

- Connection: Keep-Alive

- If - * headers

- Cache-Control or Pragma no-cache

The first three items are interrelated. HTTP 1.0 does not include compression–indicated by the Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate header, or connection keep-alives. Compression can reduce the byte count of text by 6:1 to 8:1. This often translates into a 40-50 percent reduction in size for a page. Connection: Keep-Alive will reuse TCP connections for subsequent requests and will save on the latency incurred by the 3-way hand-shake, and 4-way tear-down required for TCP connections on every request. Keeping connections open is important in emerging web-based applications that utilize Web 2.0 technology such as AJAX (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) to perform real-time updates of content because it reduces the overhead associated with opening and closing TCP connections.

The various If-* headers, such as If-Modified-Since, will enable the web server to send a response that indicates the content has not been modified if this is true. This can potentially turn a 200KB download into a 1KB download, as the browser will respond to the 304 Not Modified response by loading the referenced content from the browser’s cache. However, a lot of If-* requests for static content can result in unnecessary round trips. This can really slow end-user performance. The no-cache header and its relatives—no-store, private, must-revalidate, and proxy-revalidate—request that proxies and, sometimes, web servers not cache the response to the request. Honoring those requests can cause the servers to do a lot more work because they must always return the full content rather than enable the browser to use a cached version.

The most important web server headers, in terms of end-user performance, are:

- The HTTP version (either HTTP/1.0 or HTTP/1.1) at the beginning of the status line

- Connection: Keep-Alive/Close

- Encoding: gzip, deflate

- The various cache-control headers, especially max-age

- Content-Type:

- Date:

- Accept-Ranges: bytes

Again, the first three items are inter-related and are meant to impart the same information as when sent by the browser. The cache-control headers are very important because they can be used to store items in the browser cache and avoid future HTTP requests altogether. However, using cached data runs the risk of using out-dated data if the content changes before the cached object expires. Content-type is important for telling the browser how to handle the object. This is most important for content that the browser hands off to plug-ins (Flash, Microsoft Office documents, etc.). It is also the biggest clue to the true function of that object in the web application. Improper content types will often result in slower, but not broken web applications. The Date header is very important because it affects how the browser interprets the cache-control headers. It is important to make sure the date on the server is set correctly so that this field is accurate. The Accept-Ranges header is only important when downloading PDF documents. It enables the browser to know that it can request the PDF document one page at a time.

https://f5.com/resources/white-papers/fundamentals-of-http

Cookies

Cookies are sent by the web server to the browser as an HTTP header and used to store all sorts of information about a user’s interaction with the site. Generally speaking the use of cookies will not affect the performance of an application, unless they are encrypted for security purposes. The reason encrypted cookies can affect performance is because the web server needs to decrypt them before use, and the encryption/decryption process is resource intensive. The more encrypted cookies that are used by a site, the longer it takes for the web server to process them into a readable format.

https://support.f5.com/kb/en-us/solutions/public/5000/100/sol5157.html?sr=46612722

Vary

The HTTP Vary header, documented in RFC2616, is set by an origin web server (OWS) and contains request-header information. This information is used to determine whether a proxy server is permitted to reply to a subsequent request without re-validating the content from the OWS.

The BIG-IP HTTP cache (referred to as RAM Cache in BIG-IP versions prior to 11.0.0) uses the information from the Vary header to cache responses from the OWS. The OWS can include information within the Vary header to determine which resource the server returns in its response. For example, if a page is optimized for a particular web browser, the OWS response may return the Vary: User-Agent HTTP header. The proxy server then uses this information to determine whether to return a cached copy of the response to subsequent requests, or to query the OWS for the resource again (a subsequent client request containing a different User-Agent value forces the proxy to query the OWS for the resource again).

This behavior can require a proxy server (including the BIG-IP HTTP cache) to use up excess disk space to cache the same response.

For example:

Client A’s request for a URI contains the following header:

User-Agent: agent1

The server’s response includes the following headers:

Vary: User-Agent, Accept-Encoding

The BIG-IP system then stores the page, noting the User-Agent and Accept-Encoding headers from the client’s request.

Client B then requests the same URI, but the request has a User-Agent header containing agent2. The BIG-IP system ignores the existing cache entry (since the User-Agent is different), forwards the request to the server, and caches the response as a separate entry.

Beginning with BIG-IP 9.2, you can use the iRule CACHE::userkey <keystring> command to instruct the cache to cache the information based on the parameter that the administrator specifies. You can use this command to prevent multiple caches of the same information. Additionally, you can use the CACHE::useragent and CACHE::acceptencoding commands to override the behavior described in the previous example, such as, have a cache based on a group of User-Agent values rather than store an entry for each User-Agent header seen, and cause duplication.

For example, the following iRule sets the cache behavior based on the information that the User-Agent has on the customer’s initial request, not on honoring User-Agent or Accept-Encoding when found in the server’s Vary header:

when HTTP\_REQUEST { set user\_key "[HTTP::header User-Agent]"

CACHE::userkey $user\_key }

Note

The user_key can be defined as any string found in the HTTP request that the administrator wants to use to build cache responses.

You can use the previously listed iRule commands, even when the server does not set a Vary header, which allows the administrator to control the behavior outside of the server.

Content-Type

The MIME type of the body of the request (used with POST and PUT requests)

Host

The host value is represented by the domain name of the server (for virtual hosting), and the TCP port number on which the server is listening. The port number may be omitted if the port is the standard port for the service requested.

2.06 - Explain HTTP methods (GET, POST, etc.)

https://f5.com/resources/white-papers/fundamentals-of-http

http://www.w3.org/Protocols/rfc2616/rfc2616-sec9.html

HTTP Methods

When you open up a browser and request a web page (either by setting a default page or by entering a Uniform Resource Locater or URL), the first thing that happens is that the browser relies upon the operating system to resolve the host name in the URL to an IP address. Normally this is done via a DNS (Domain Name System) query over UDP (User Datagram Protocol) on port 53. However, if the host is listed in the local hosts file, the operating system will not make a DNS query.

When the IP address is obtained, the browser will attempt to open a TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) connection to the web server, usually on port 80. Once the TCP connection is made, the browser will issue an HTTP request to the server using the connection. The request comprises a header section, and possibly a body section (this is where things like POST data go). Once the request is sent, the browser will wait for the response. When the web server has assembled the response, it is sent back to the browser for rendering.

The base request comprises a method, the URI (Uniform Resource Indicator) of the web page or resource being requested, and the HTTP version desired (1.0 or 1.1). The method may be one of:

- Get

- Post

- Put

- Delete

- Head

Web servers almost universally support GET and POST, with the difference between them being the way in which query parameters are represented. With the GET method, all query parameters are part of the URI. This restricts the length of the parameters because a URI is generally limited to a set number of characters. Conversely, all parameters are included within the body of the request when using the POST method and there is usually no limit on the length of the body. PUT and DELETE, though considered important for emerging technology architectures such as REST (Representational State Transfer), are considered potentially dangerous as they enable the user to modify resources on the web server. These methods are generally disabled on web servers and not supported by modern web browsers.

The HTTP response consists of a header section and a body. The header section tells the browser how to treat the body content and the browser renders the content for viewing. Each HTTP response includes a status code, which indicates the status of the request. The most common status codes are:

200 OK. This indicates success

304 Not Modified. This shows that the resource in question has not changed and the browser should load it from its cache instead. This is only used when the browser performs a conditional GET request.

404 Not Found. This suggests that the resource requested cannot be found on the server.

401 Authorization Required. This indicates that the resource is protected and requires valid credentials before the server can grant access.

500 Internal Error. This signifies that the server had a problem processing the request.

While most developers do not need to know these status codes as they are not used within D/HTML, AJAX (Asynchronous Javascript and XML) developers may need to recognize these codes as part of their development efforts.

Most HTTP responses will also contain references to other objects within the body that will cause the browser to automatically request these objects as well. Web pages often contain more than 30 other object references required to complete the page.

When retrieving these referenced objects, the default browser behavior is to open two TCP connections per host seen in the references. With Internet Explorer there is a Windows registry setting that limits this to a total of eight TCP connections. There is a similar setting in Firefox, but its maximum is 24 TCP connections.

Get